Search -

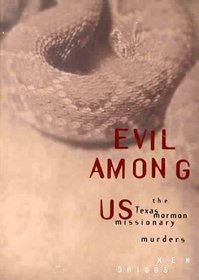

Evil Among Us: The Texas Mormon Missionary Murders

Evil Among Us The Texas Mormon Missionary Murders

Author:

Introduction About a year after arriving in Texas in 1993 as an attorney, I chanced upon newspaper reports of the 1974 incredibly brutal murders of young Mormon missionaries Gary Darley and Mark Fischer. I recalled hearing about them years earlier in my own LDS congregation when the news first broke, and started investigating the case with an ey... more »

Author:

Introduction About a year after arriving in Texas in 1993 as an attorney, I chanced upon newspaper reports of the 1974 incredibly brutal murders of young Mormon missionaries Gary Darley and Mark Fischer. I recalled hearing about them years earlier in my own LDS congregation when the news first broke, and started investigating the case with an ey... more »

ISBN-13: 9781560851387

ISBN-10: 1560851384

Publication Date: 8/2000

Pages: 290

Rating: 1

ISBN-10: 1560851384

Publication Date: 8/2000

Pages: 290

Rating: 1

3 stars, based on 1 rating

Genres: