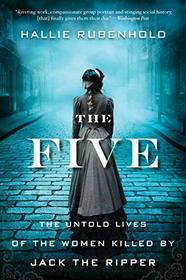

This book never felt slow because it frequently read like a novel. I learned so much about these five women who came alive through their circumstances. They weren't the "prostitutes" everyone assumed they were and Jack the Ripper preyed on these women because they were sleeping outside due to lack of money, family and Victorian prejudices. The book also explains how the data about these women is divergent and contradictory. A very good book, which educates and entertains.

"I write for those women who do not speak, for those who do not have a voice because they were so terrified, because we are taught to respect fear more than ourselves. We've been taught that silence would save us, but it won't."

-Audre Lorde

The entire premise of this exhaustively researched social history is laudable: even in this famous case, typically, as usual, the names of the victims are spoken only in passing, and even then, the attention is almost always squarely focused on the killer, in this case, the nameless murderer known only by his sensationalized moniker, an invention of an enterprising newspaperman looking to sell an image of horror. The five women the killer brutalized, tortured and slaughtered on the streets of Victorian London often appear as little more than footnotes. Discussion of their bleak lives typically take the form of lurid descriptions of their hideous wounds, sometimes placed in the historical context of the squalid and violent surroundings in which they spent their short lives.

This thorough history, in contrast, treats the women as the individuals they were: mothers, daughters, sisters, wives, lovers, friends, and persons with aspirations and lives all their own. This attempt at "re-centering the margins" is long overdue in this particular sub-genre of "true crime." Poignantly, the author writes: "They were worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for... The courses their lives took mirrored that of so many other women of the Victorian age; and yet were so singular in the way they ended. It is for them that I write this book. I do so in the hope that we may now hear their stories clearly and give back to them that which was so brutally taken away with their lives: their dignity." It juxtaposes the splendor of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebration, with all its pomp and pageantry, with the lives of ordinary working Londoners and migrants, and the disparity is striking.

It's remarkable that so much evidence exists about the five women described herein. One of the most startling claims made by the book is that, despite their unfortunate circumstances, potentially only one of the victims was actually a prostitute. The general attitude of the day was that all women in such standing at some point were sex workers, but the author does an admirable job in dispelling this generalization. Another important factor to consider is that, if the murderer was not, in fact, targeting prostitutes, who were his intended victims? According to Rubenhold, the killer, far from luring them into dark alleys for sex, instead simply targeted women while they slept. She wisely questions some of the information which has hitherto been taken largely at face value, choosing to eschew many of the salacious newspaper reports about the murders and "witness" accounts who were completely unfamiliar with the women or their activities at all before they were killed.

The portrait illustrated here suggests that, in contrast to the specific targeting of "fallen" unfortunates, classifying the killings as what would today be called "public service" murders, where a killer acts out of the belief that they are helping to "clean up" an area or community, or to root out vice, the victims here were targeted simply because they were women: homeless, indigent, and sleeping "rough" out in the open, with no protection from the elements or from those who wished to do them harm, the murderer simply killed any defenseless woman he happened upon. Rubenhold notes that nearly all of the victims were killed in a reclining position, suggesting that, with the lack of noise or apparent struggle, the victims were simply attacked while they slept. This practice would also be in keeping with several modern-day cases of serial killers who target the homeless. It would also raise the question as to whether any men were similarly attacked; if the police and investigators erroneously believed that the only victims were prostitutes, they may not have connected attacks on male victims, as a cut throat was far from uncommon in the seedy slums of Victorian London.

What the book does do, in exquisite detail, is chronicle the lives of the five individuals murdered in Whitechapel in the summer and fall of 1888. It particularly emphasizes their humanity, describing them as people, albeit those who could not escape their humble birth and station, and whose lives ended tragically, but not as abbreviated as many often assume: none but one of the women were what would be considered young, as all but the last victim were in their forties when they died, several with grown children. The book also provides a detailed portrait of life in late-nineteenth-century London, in the wake of rapid industrialization and social change, which caused great upheaval to traditional modes of life, as people flooded into the great city from near and far, and sometimes abroad. As a result, the city had already reached a population of more than a million, which strained its infrastructure to the breaking point.

The vanished world (much of east London, particularly the Whitechapel district, was obliterated by the blitz during World War II, and was subsequently rebuilt-little of what would have been familiar to the victims thus remains intact today) revealed by the ample descriptions is a bleak one, dominated by crushing poverty, great disparity of wealth, chronic unemployment, addiction and domestic violence. It's a world of soldiers and sailors, itinerant workers, child labor, workhouses, malnutrition, frequent homelessness and vagrancy, which was inescapable for all but the fortunate few.

It's also a world rife with untimely death: life expectancy was typically the mid-forties, for both men and women - men died prematurely from violence, disease and accident, while women frequently died either in childbirth or from complications stemming from an endless cycle of pregnancy and child bearing, in addition to overwork and exposure to insalubrious surroundings that also accounted for an appalling child mortality rate. Rare was the woman who had not lost at least one child, and, in the case of one of the victims, four of her six children to infectious disease.

If you're looking for an account of how the women were murdered, or a description of them after, you'll be disappointed. This book, rightly, considering its purpose, eschews almost any mention of the actual murders or of the killer, in favor of a focus on the individuals who were slaughtered in the streets, probably while they slept. This book is a welcome addition to the often-sensationalized account of this series of events, which humanizes the victims and gives them a voice in a way few thought possible - indeed, none have attempted such a feat previously. The solid and convincing research enhances the moving and poignant descriptions of the lives of both the women and those around them.

------------

"[The lives of the victims] became entangled in a web of assumptions, rumor and unfounded speculation. The spinning of these strands began over 130 years ago and, remarkably, they have been left virtually undisturbed and unchallenged. The fibers that have clung to and defined the shape of Polly, Annie Elisabeth, Kate and Mary Jane's stories are the values of the Victorian world. They are male, authoritarian, and middle class. They were formed at a time when women had no voice, and few rights, and the poor were considered lazy and degenerate; to have been both of these things was one of the worst possible combinations. For over 130 years, we have embraced the dusty parcel we were handed. We have rarely ventured to peer inside it or attempted to remove the thick wrapping that has kept us from knowing these women or their true histories."

-Audre Lorde

The entire premise of this exhaustively researched social history is laudable: even in this famous case, typically, as usual, the names of the victims are spoken only in passing, and even then, the attention is almost always squarely focused on the killer, in this case, the nameless murderer known only by his sensationalized moniker, an invention of an enterprising newspaperman looking to sell an image of horror. The five women the killer brutalized, tortured and slaughtered on the streets of Victorian London often appear as little more than footnotes. Discussion of their bleak lives typically take the form of lurid descriptions of their hideous wounds, sometimes placed in the historical context of the squalid and violent surroundings in which they spent their short lives.

This thorough history, in contrast, treats the women as the individuals they were: mothers, daughters, sisters, wives, lovers, friends, and persons with aspirations and lives all their own. This attempt at "re-centering the margins" is long overdue in this particular sub-genre of "true crime." Poignantly, the author writes: "They were worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for... The courses their lives took mirrored that of so many other women of the Victorian age; and yet were so singular in the way they ended. It is for them that I write this book. I do so in the hope that we may now hear their stories clearly and give back to them that which was so brutally taken away with their lives: their dignity." It juxtaposes the splendor of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebration, with all its pomp and pageantry, with the lives of ordinary working Londoners and migrants, and the disparity is striking.

It's remarkable that so much evidence exists about the five women described herein. One of the most startling claims made by the book is that, despite their unfortunate circumstances, potentially only one of the victims was actually a prostitute. The general attitude of the day was that all women in such standing at some point were sex workers, but the author does an admirable job in dispelling this generalization. Another important factor to consider is that, if the murderer was not, in fact, targeting prostitutes, who were his intended victims? According to Rubenhold, the killer, far from luring them into dark alleys for sex, instead simply targeted women while they slept. She wisely questions some of the information which has hitherto been taken largely at face value, choosing to eschew many of the salacious newspaper reports about the murders and "witness" accounts who were completely unfamiliar with the women or their activities at all before they were killed.

The portrait illustrated here suggests that, in contrast to the specific targeting of "fallen" unfortunates, classifying the killings as what would today be called "public service" murders, where a killer acts out of the belief that they are helping to "clean up" an area or community, or to root out vice, the victims here were targeted simply because they were women: homeless, indigent, and sleeping "rough" out in the open, with no protection from the elements or from those who wished to do them harm, the murderer simply killed any defenseless woman he happened upon. Rubenhold notes that nearly all of the victims were killed in a reclining position, suggesting that, with the lack of noise or apparent struggle, the victims were simply attacked while they slept. This practice would also be in keeping with several modern-day cases of serial killers who target the homeless. It would also raise the question as to whether any men were similarly attacked; if the police and investigators erroneously believed that the only victims were prostitutes, they may not have connected attacks on male victims, as a cut throat was far from uncommon in the seedy slums of Victorian London.

What the book does do, in exquisite detail, is chronicle the lives of the five individuals murdered in Whitechapel in the summer and fall of 1888. It particularly emphasizes their humanity, describing them as people, albeit those who could not escape their humble birth and station, and whose lives ended tragically, but not as abbreviated as many often assume: none but one of the women were what would be considered young, as all but the last victim were in their forties when they died, several with grown children. The book also provides a detailed portrait of life in late-nineteenth-century London, in the wake of rapid industrialization and social change, which caused great upheaval to traditional modes of life, as people flooded into the great city from near and far, and sometimes abroad. As a result, the city had already reached a population of more than a million, which strained its infrastructure to the breaking point.

The vanished world (much of east London, particularly the Whitechapel district, was obliterated by the blitz during World War II, and was subsequently rebuilt-little of what would have been familiar to the victims thus remains intact today) revealed by the ample descriptions is a bleak one, dominated by crushing poverty, great disparity of wealth, chronic unemployment, addiction and domestic violence. It's a world of soldiers and sailors, itinerant workers, child labor, workhouses, malnutrition, frequent homelessness and vagrancy, which was inescapable for all but the fortunate few.

It's also a world rife with untimely death: life expectancy was typically the mid-forties, for both men and women - men died prematurely from violence, disease and accident, while women frequently died either in childbirth or from complications stemming from an endless cycle of pregnancy and child bearing, in addition to overwork and exposure to insalubrious surroundings that also accounted for an appalling child mortality rate. Rare was the woman who had not lost at least one child, and, in the case of one of the victims, four of her six children to infectious disease.

If you're looking for an account of how the women were murdered, or a description of them after, you'll be disappointed. This book, rightly, considering its purpose, eschews almost any mention of the actual murders or of the killer, in favor of a focus on the individuals who were slaughtered in the streets, probably while they slept. This book is a welcome addition to the often-sensationalized account of this series of events, which humanizes the victims and gives them a voice in a way few thought possible - indeed, none have attempted such a feat previously. The solid and convincing research enhances the moving and poignant descriptions of the lives of both the women and those around them.

------------

"[The lives of the victims] became entangled in a web of assumptions, rumor and unfounded speculation. The spinning of these strands began over 130 years ago and, remarkably, they have been left virtually undisturbed and unchallenged. The fibers that have clung to and defined the shape of Polly, Annie Elisabeth, Kate and Mary Jane's stories are the values of the Victorian world. They are male, authoritarian, and middle class. They were formed at a time when women had no voice, and few rights, and the poor were considered lazy and degenerate; to have been both of these things was one of the worst possible combinations. For over 130 years, we have embraced the dusty parcel we were handed. We have rarely ventured to peer inside it or attempted to remove the thick wrapping that has kept us from knowing these women or their true histories."

This book tells the story of the five women killed by Jack the Ripper. This book is well-researched and tightly written. So that you know, this is not a book about Jack the Ripper. Interestingly, the author wants to remove these women (as much as possible) from the label of prostitution. So instead, the author concentrates on these women's dreary, dismal lives, trying to eke out a simple existence. The young women's names were Annie, Catherine, Elizabeth, Mary-Jane, and Polly (Mary Ann). This book turns these women into people instead of simply nameless victims.

This book shows Victorian British women's difficulty caring for themselves without a husband's support. The police generally labeled any unwed woman, on her own, as a prostitute. Polly (Mary Ann Nichols), the first victim, lost her husband to another woman (a neighbor). After her husband removed his support, Polly became a wandering person, just looking for pennies to find a night's lodging.

While the newspapers were still telling about Polly's murder, Annie Chapman became the next victim. Years earlier, Annie succumbed to liquor and lost her husband. His boss would not have a drunkard near his fashionable estate, and Annie's husband reluctantly turned Annie out. When Annie's husband's weekly support did not arrive, she walked miles to find that her husband was dying. Annie fell apart with grief. At the same time, she was suffering from tuberculosis. However, she generally sold her crochet and needlework to earn a bed for the night.

Elizabeth Stride's story is even more pitiful. Becoming a housemaid at seventeen, someone in the household seduced Elizabeth. By twenty-one (years old), Elizabeth had lost a baby and was treated for venereal disease (an excruciating, dangerous, and humiliating exercise involving the police). Eventually, Elizabeth married, but the marriage fell apart, possibly because Elizabeth could not have children (or at least carry them to term, probably because of latent venereal disease). Eventually, she fell into prostitution. However, she also demonstrated the terminal effects of the neuro-venereal disease (epileptic seizures, disorientation, etc.). Another victim was found on the same night that Elizabeth left this earth.

If possible, Catherine Eddowes's story is even more pathetic. After her parents died of illnesses, the many Eddowes children quickly married or were sent to workhouses. Catherine received a workhouse education until she was sent to an uncle to find work. Catherine soon left their home and followed a traveling hawker (salesman of chapter books). They had multiple children. He never married Catherine but beat her regularly. Eventually, the family broke apart, and Catherine struck out independently. Finally, after years of 'living rough,' Catherine was found the same night as Elizabeth in Whitechapel.

About six weeks after this pair of deaths, the youngest victim would die - Mary Jane Kelly. This young woman changed her story so much that people did not know if she was Welsh or Irish. No information Mary Jane gave was ever confirmed; the woman who died is unknown. However, she was an attractive woman used to the sex trade. Eventually, Mary Jane took up with a fellow drinker (Joe Barnett), and they lived together for eighteen months until he lost his job. After the couple argued, Barnett left. Hours later, Mary Jane was found in her bed.

Alcohol destroyed each of these women's lives. This book is a sociological study of lower-class lives during the Victorian Era. This compelling book turns these statistics into tragic, complex beings before their gruesome deaths. The story does not include the details of the women's deaths, which would have taken from the consequence of their lives. This is probably the most important book I've read this year. The author's research shines on every page of this book; absolutely brilliant.

This book shows Victorian British women's difficulty caring for themselves without a husband's support. The police generally labeled any unwed woman, on her own, as a prostitute. Polly (Mary Ann Nichols), the first victim, lost her husband to another woman (a neighbor). After her husband removed his support, Polly became a wandering person, just looking for pennies to find a night's lodging.

While the newspapers were still telling about Polly's murder, Annie Chapman became the next victim. Years earlier, Annie succumbed to liquor and lost her husband. His boss would not have a drunkard near his fashionable estate, and Annie's husband reluctantly turned Annie out. When Annie's husband's weekly support did not arrive, she walked miles to find that her husband was dying. Annie fell apart with grief. At the same time, she was suffering from tuberculosis. However, she generally sold her crochet and needlework to earn a bed for the night.

Elizabeth Stride's story is even more pitiful. Becoming a housemaid at seventeen, someone in the household seduced Elizabeth. By twenty-one (years old), Elizabeth had lost a baby and was treated for venereal disease (an excruciating, dangerous, and humiliating exercise involving the police). Eventually, Elizabeth married, but the marriage fell apart, possibly because Elizabeth could not have children (or at least carry them to term, probably because of latent venereal disease). Eventually, she fell into prostitution. However, she also demonstrated the terminal effects of the neuro-venereal disease (epileptic seizures, disorientation, etc.). Another victim was found on the same night that Elizabeth left this earth.

If possible, Catherine Eddowes's story is even more pathetic. After her parents died of illnesses, the many Eddowes children quickly married or were sent to workhouses. Catherine received a workhouse education until she was sent to an uncle to find work. Catherine soon left their home and followed a traveling hawker (salesman of chapter books). They had multiple children. He never married Catherine but beat her regularly. Eventually, the family broke apart, and Catherine struck out independently. Finally, after years of 'living rough,' Catherine was found the same night as Elizabeth in Whitechapel.

About six weeks after this pair of deaths, the youngest victim would die - Mary Jane Kelly. This young woman changed her story so much that people did not know if she was Welsh or Irish. No information Mary Jane gave was ever confirmed; the woman who died is unknown. However, she was an attractive woman used to the sex trade. Eventually, Mary Jane took up with a fellow drinker (Joe Barnett), and they lived together for eighteen months until he lost his job. After the couple argued, Barnett left. Hours later, Mary Jane was found in her bed.

Alcohol destroyed each of these women's lives. This book is a sociological study of lower-class lives during the Victorian Era. This compelling book turns these statistics into tragic, complex beings before their gruesome deaths. The story does not include the details of the women's deaths, which would have taken from the consequence of their lives. This is probably the most important book I've read this year. The author's research shines on every page of this book; absolutely brilliant.

A fantastic piece of research, drawing together the details of the lives of five ordinary, all-too-typical working class women who, were it not for the terrible circumstances of their deaths at the hands of one of history's most notorious killers, would have remained completely anonymous and lost to history.

Fascinating, even if you have no interest whatsoever in the -- what can I call it, without being rude -- "mythology" ... obsession? -- of Jack the Ripper. This is a window into the downward spiral of the lives of five very different women of Victorian London, who illustrate all too painfully how most working class people of that era lived on the edge of an abyss, and how one life crisis -- illness, loss of employment, death of a parent or spouse, collapse of a relationship -- could plunge them headlong into destitution, homelessness, and a life in the shadows, beyond the respectability and minimal comforts they had worked so hard to enjoy.

There was nothing quaint or historical about Rubenhold's descriptions of pathetic figures, roaming the streets at all hours of the night, trying to beg, borrow or steal the price of a flea-infested bed in one of the doss houses in the East End of London, That could be now.

This is a book that has gotten under my skin -- and that's a very good thing for a book, I hope you will agree. Rubenhold's research is amazing. Her writing is very readable. The subject, taking the spotlight from the homicidal maniac, and refocusing it on the victims, and their lives, rather than their gruesome deaths -- in other words, giving them back their dignity, and their humanity -- is important.

HIGHLY recommended.

Fascinating, even if you have no interest whatsoever in the -- what can I call it, without being rude -- "mythology" ... obsession? -- of Jack the Ripper. This is a window into the downward spiral of the lives of five very different women of Victorian London, who illustrate all too painfully how most working class people of that era lived on the edge of an abyss, and how one life crisis -- illness, loss of employment, death of a parent or spouse, collapse of a relationship -- could plunge them headlong into destitution, homelessness, and a life in the shadows, beyond the respectability and minimal comforts they had worked so hard to enjoy.

There was nothing quaint or historical about Rubenhold's descriptions of pathetic figures, roaming the streets at all hours of the night, trying to beg, borrow or steal the price of a flea-infested bed in one of the doss houses in the East End of London, That could be now.

This is a book that has gotten under my skin -- and that's a very good thing for a book, I hope you will agree. Rubenhold's research is amazing. Her writing is very readable. The subject, taking the spotlight from the homicidal maniac, and refocusing it on the victims, and their lives, rather than their gruesome deaths -- in other words, giving them back their dignity, and their humanity -- is important.

HIGHLY recommended.