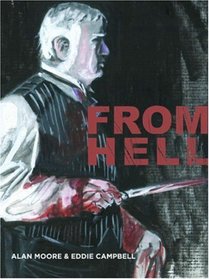

After Swamp Thing and Watchmen brought fame and fortune to Alan Moore, the man who practically redefined the "comic book" medium and popularized the form for serious literature, he spent the better part of the late 1980s through the mid-1990s attempting to bring more "serious" works of graphic literature into existence. But because the comic book market is still dominated by superheroes, Moore's struggled through an uphill battle to succedully release even one of the various projects he attempted. Big Numbers remains tantalizingly incomplete, with only the first few chapters of each being successfully published; while Lost Girls was finally published in 2006, more than fifteen years after the first chapters appeared in Eddie Campbell]'s Taboo magazine. As for Moore's third major project, it took more than a decade for all ten books of From Hell (plus its appendix, "Dance of the Gull Catchers") to see the light of day.

It was worth the wait.

Studied Ripperologists have praised Moore for the obsessive, painstakingly detailed research he undertook into the subject of the Whitechapel murders, unearthing buried facts and exploring most if not all of the various conspiracy theories involving the Royal Family, the Freemasons, Scotland Yard, and just about anyone who was involved with the Victorian aristrocracy of the time. But Moore is first and foremost a storyteller, and From Hell earns the title "masterwork" by being more than merely a scholarly journal. It's a taut, horrific, mesmerizing journey into madness that is both a fascinating detective story worthy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; and it's also a haunting, poetic journey reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe. But Moore's mastery of the medium of graphic literature â" backed by the superb and appropriately sketchy artistry of Eddie Campbell â" weaves the various threads together into a fabric that conjures up images of the sights, smells, thoughts, and fears of the Victorian Era in a way that makes the reader glad that the world has changed since those days.

It has, rather, devolved into something far worse.

Our fascination with Jack the Ripper, Moore hypothesizes, is a reflection of ourselves, and the society that we have become. (These insights become especially clear during Chapter 10, "The Best Of All Tailors" â" as the Ripper chastises us for allowing ourselves to become numb and soulless, while engaging in one of the most horrifying and bloody murder scenes ever displayed in any graphic medium, anywhere.) But if the polluted, diseased world of Victorian London is not really much worse than our own, then we can at least thank Alan Moore for presenting us with a fascinating tale that gives us a glimpse into itâ¦a view that has never been presented to us in this manner before, with all of its horrors laid bare for us to see. Even more so than Watchmen, From Hell is a shining example of the very finest achievements of graphic literature. This, dear friends, is no comic book.

It was worth the wait.

Studied Ripperologists have praised Moore for the obsessive, painstakingly detailed research he undertook into the subject of the Whitechapel murders, unearthing buried facts and exploring most if not all of the various conspiracy theories involving the Royal Family, the Freemasons, Scotland Yard, and just about anyone who was involved with the Victorian aristrocracy of the time. But Moore is first and foremost a storyteller, and From Hell earns the title "masterwork" by being more than merely a scholarly journal. It's a taut, horrific, mesmerizing journey into madness that is both a fascinating detective story worthy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; and it's also a haunting, poetic journey reminiscent of Edgar Allan Poe. But Moore's mastery of the medium of graphic literature â" backed by the superb and appropriately sketchy artistry of Eddie Campbell â" weaves the various threads together into a fabric that conjures up images of the sights, smells, thoughts, and fears of the Victorian Era in a way that makes the reader glad that the world has changed since those days.

It has, rather, devolved into something far worse.

Our fascination with Jack the Ripper, Moore hypothesizes, is a reflection of ourselves, and the society that we have become. (These insights become especially clear during Chapter 10, "The Best Of All Tailors" â" as the Ripper chastises us for allowing ourselves to become numb and soulless, while engaging in one of the most horrifying and bloody murder scenes ever displayed in any graphic medium, anywhere.) But if the polluted, diseased world of Victorian London is not really much worse than our own, then we can at least thank Alan Moore for presenting us with a fascinating tale that gives us a glimpse into itâ¦a view that has never been presented to us in this manner before, with all of its horrors laid bare for us to see. Even more so than Watchmen, From Hell is a shining example of the very finest achievements of graphic literature. This, dear friends, is no comic book.

Well, I finished around four in the morning after getting it in the mail the previous afternoon, so I think I have to give it a thumbs-up.

The book is a graphic novel written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Eddie Campbell about Jack the Ripper. Detailing events leading up to the infamous Whitechapel murders and an ensuing coverup, "From Hell" is a tightly scripted piece of historical fiction.

The book did not disappoint. It was a tightly written graphic novel, as meticulously plotted as I've come to expect from Alan Moore, and thoroughly researched. The book is structured around a widely dismissed conspiracy theory that Jack the Ripper's actions were a plot orchestrated by the Freemasons to protect the British Crown during the reign of Queen Victoria from a scandal involving her grandson Albert.

The action is gruesome -- this is a story about Jack the Ripper, after all -- but Moore's ability to tap into the power of symbolism and to further imbue those symbols with the semblance of deeper order and power, drives some of the most absorbing sections of the book, such as Sir William Gull's taxi ride back and forth across London as he completes an arcane circuit of the city's churches and landmarks.

On the downside, the artwork did make it difficult at times to differentiate among the characters, particularly given the size of the cast; and as an American reader unfamiliar with 19th-century London slang, customs or culture, I had to consult Wikipedia at times to make sure I was following the story correctly. (I also had to re-read the first two chapters, since I found I didn't understand properly what was happening in the fourth chapter, when the story started to progress.)

The artwork also was explicit, not just in terms of the violence, but also regarding human sexuality. Jack the Ripper, after all, wasn't just a serial killer; he was driven by psychosexual demons that led him to prey upon prostitutes in the Whitechapel district with a particularly vicious sexual violence. As a result, I doubt I'll be letting my daughter read this anytime soon. Maybe around the time I let her read my "Swamp Thing" collections, which I've summed up previously as "When you're older, and I'm dead."

I do recommend it, although if you've decided you're not an Alan Moore fan, I concede that you probably won't like it.

* I think I finally enjoyed "Watchmen" on the fifth or sixth time through. To be fair, on first reading I think I initially was expecting a superhero comic, and wasn't ready for the superhero deconstructed. By the time I was in my early 30s, though, I was finally able to see myself a little in Nite Owl, and could appreciate better what Moore had done with the other nonheroic "superheroes" like Dr. Manhattan and Rorshach.

The book is a graphic novel written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Eddie Campbell about Jack the Ripper. Detailing events leading up to the infamous Whitechapel murders and an ensuing coverup, "From Hell" is a tightly scripted piece of historical fiction.

The book did not disappoint. It was a tightly written graphic novel, as meticulously plotted as I've come to expect from Alan Moore, and thoroughly researched. The book is structured around a widely dismissed conspiracy theory that Jack the Ripper's actions were a plot orchestrated by the Freemasons to protect the British Crown during the reign of Queen Victoria from a scandal involving her grandson Albert.

The action is gruesome -- this is a story about Jack the Ripper, after all -- but Moore's ability to tap into the power of symbolism and to further imbue those symbols with the semblance of deeper order and power, drives some of the most absorbing sections of the book, such as Sir William Gull's taxi ride back and forth across London as he completes an arcane circuit of the city's churches and landmarks.

On the downside, the artwork did make it difficult at times to differentiate among the characters, particularly given the size of the cast; and as an American reader unfamiliar with 19th-century London slang, customs or culture, I had to consult Wikipedia at times to make sure I was following the story correctly. (I also had to re-read the first two chapters, since I found I didn't understand properly what was happening in the fourth chapter, when the story started to progress.)

The artwork also was explicit, not just in terms of the violence, but also regarding human sexuality. Jack the Ripper, after all, wasn't just a serial killer; he was driven by psychosexual demons that led him to prey upon prostitutes in the Whitechapel district with a particularly vicious sexual violence. As a result, I doubt I'll be letting my daughter read this anytime soon. Maybe around the time I let her read my "Swamp Thing" collections, which I've summed up previously as "When you're older, and I'm dead."

I do recommend it, although if you've decided you're not an Alan Moore fan, I concede that you probably won't like it.

* I think I finally enjoyed "Watchmen" on the fifth or sixth time through. To be fair, on first reading I think I initially was expecting a superhero comic, and wasn't ready for the superhero deconstructed. By the time I was in my early 30s, though, I was finally able to see myself a little in Nite Owl, and could appreciate better what Moore had done with the other nonheroic "superheroes" like Dr. Manhattan and Rorshach.