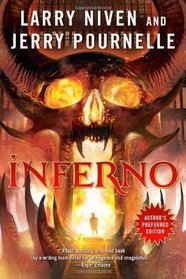

Into the fantastic abyss of an ingenious, living hell....

An unearthly voice hisses unholy welcome. And the late, great Allen Carpentier begins his one-way journey into the dim nether regions where flame-colored demons wield diabolically sharp pitchforks and tormented vixens reign forever in a pond of sheer ice. Here, in this land of torment and terror, he discovers the amazing truth of the ultimate adventure that lies beyond the grave.

"The somber beauty of INFERNO brought up to the twentieth century with care and humor and with some sins Dante didn't even suspect."

---Frank Herbert, author of Dune

An unearthly voice hisses unholy welcome. And the late, great Allen Carpentier begins his one-way journey into the dim nether regions where flame-colored demons wield diabolically sharp pitchforks and tormented vixens reign forever in a pond of sheer ice. Here, in this land of torment and terror, he discovers the amazing truth of the ultimate adventure that lies beyond the grave.

"The somber beauty of INFERNO brought up to the twentieth century with care and humor and with some sins Dante didn't even suspect."

---Frank Herbert, author of Dune

I just finished re-reading "Inferno" for what is probably the seventh or eighth time.

Niven and Pournelle, predictably, set their story around a sci-fi writer who dies at a sci-fi convention and finds himself in hell. The book probably would have benefitted from another draft. Because the narrator is a sci-fi writer, much of the book is dominated by sci-fi talk, as the writer tries to find scientic explanations for what he encounters. And because it's a Niven book, it's chock-full of sly and not-so-subtle references to his other works. It gets a little distracting.

Still, readers will get is a perverse kick out of seeing whom Niven and Journelle have placed among the ranks of the damned. There's Himuralabima, who invented bureaucracy; one of Niven's own fictional characters, from "A Time out of Mind"; the two authors themselves, presumably, in the identity of the main character; and Billy the Kid, among others. There's just enough information given in a few cases to identify other real people who were alive at the time of the book's publication, such as Kurt Vonnegut.

And part of it is also the hauntingly funereal beauty of the setting, which comes through despite the narrator's missing-the-point efforts to explain what he sees. The pit of flatterers remains grossly appropriate, as do the other ironic endings the authors describe: politicians frozen in the ice because they betrayed their own consciences for the sake of party loyalty, bulldozers that chase real estate developers, and the disinterested cruelty of the demons.

In the end, "Inferno" moves from being merely an updated vision of Dante's work, to a commentary on the work and on the doctrine of hell itself. I have no answers myself, just questions that echo in my own soul when I read this book, and that itself is a triumph of sorts, and why I keep reading it.

Niven and Pournelle, predictably, set their story around a sci-fi writer who dies at a sci-fi convention and finds himself in hell. The book probably would have benefitted from another draft. Because the narrator is a sci-fi writer, much of the book is dominated by sci-fi talk, as the writer tries to find scientic explanations for what he encounters. And because it's a Niven book, it's chock-full of sly and not-so-subtle references to his other works. It gets a little distracting.

Still, readers will get is a perverse kick out of seeing whom Niven and Journelle have placed among the ranks of the damned. There's Himuralabima, who invented bureaucracy; one of Niven's own fictional characters, from "A Time out of Mind"; the two authors themselves, presumably, in the identity of the main character; and Billy the Kid, among others. There's just enough information given in a few cases to identify other real people who were alive at the time of the book's publication, such as Kurt Vonnegut.

And part of it is also the hauntingly funereal beauty of the setting, which comes through despite the narrator's missing-the-point efforts to explain what he sees. The pit of flatterers remains grossly appropriate, as do the other ironic endings the authors describe: politicians frozen in the ice because they betrayed their own consciences for the sake of party loyalty, bulldozers that chase real estate developers, and the disinterested cruelty of the demons.

In the end, "Inferno" moves from being merely an updated vision of Dante's work, to a commentary on the work and on the doctrine of hell itself. I have no answers myself, just questions that echo in my own soul when I read this book, and that itself is a triumph of sorts, and why I keep reading it.

![header=[] body=[Get a free book credit right now by joining the club and listing 5 books you have and are willing to share with other members!] Help icon](/images/question.gif?v=5fea88b8)