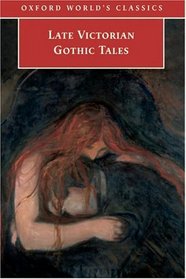

I've been reading a lot of literature from this period recently, but this is a unique volume. It includes more than just "ghost stories," but tales from this transformative period which reflect its most prominent characteristics. I liked that it included some of the Tales from the Empire, along with others which reflect an element of increasing globalization, and a veritable lack of comfort with what the colonizers were encountering. There is certainly an element of "Orientalizing" in the stories, which are replete with an otherworldly exoticism that's also somewhat uncomfortable for modern readers, but perhaps for a different reason.

The volume is overall, as some other reviewers have noted, a collection of those things, some seemingly mundane, which disturbed Victorian authors and readers, who were increasingly encountering a changing world. As the introduction noted, the literature, like society and the prevailing culture and attitudes during the day, were transgressive and challenging of an old established order, which changed forever with the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. It's also something of an ominous warning of what was to come in the 20th century, just a few short years away, and the atrocity which no one could have contemplated.

I included some of the most important passages from the introduction below, as I think they do an admirable job of describing and defining "Gothic," a term not well understood in the modern sense, aside perhaps from the systematic challenging and transgression of borders and boundaries, where rules break down and life is lived in the margins. This is a worthwhile volume with some truly spooky and unsettling tales, well worth a read if you're a fan of suspense fiction: it certainly highlights the anxieties and insecurities of people of the period, who faced an evermore speedily changing world.

--------Important Passages--------

The Gothic repeatedly stages moments of transgression because it is obsessed with establishing and policing borders, delineating strict categories of being. The enduring icons of the Gothic are entities that breach the absolute distinctions between life and death (ghosts, vampires, mummies, zombies, Frankenstein's creature) or between human and beast (werewolves and other animalistic regressions, the creatures spliced together by Dr. Moreau) or which threaten the integrity of the individual ego and the exercise of will by merging with another (Jeckyll and Hyde, the persecuting double, the Mesmerist who holds victims in his or her power). Ostensibly, conclusions reinstate fixed borders, re-secure autonomy, and destroy any intolerable occpants of these twilight zones.

The most succssful mosters overdetermine these tansgressions to become, in Judith Halberstam's evocative phrase, 'technologies of monstrosity' that condense and process different and even contradictory anxieties about category and border. Some critics hold that the genre speaks to universal, primitive taboos about the very foundational elements of what it means to be human, yet the ebb and flow of the Gothic across the modern period invites more historical readings. Indeed, one of the princial border breaches in the Gothic is history itself- the insidious leakage of the pre-modern past into the skeptical, allegedly enlightened present. The Gothic, Robert Mighall suggests, can be thought of as a way of relating to the past and its legacies.

We can think about this in fairly abstract ways: the ghost, for instance, is structurally a stubborn trace of the past that persists into the present and demands a historical understanding if it is to be laid to rest. Similarly, Sigmund Freud defined the feeling of the uncanny as the shiver of realizing that modern reason has merely repressed rather than replaced primitive superstition. 'All supposedly educated people have ceased to believe officailly that the dead can become visible as spirits', yet Freud suspeccted that at times 'almost all of us think as savages do on this topic.' This return to pre-modern beliefs was itself the product of thinking of human subjectivity as a history of developmental layers that could be stripped away in an instant of dread, returning us to a 'savage' state.

The volume is overall, as some other reviewers have noted, a collection of those things, some seemingly mundane, which disturbed Victorian authors and readers, who were increasingly encountering a changing world. As the introduction noted, the literature, like society and the prevailing culture and attitudes during the day, were transgressive and challenging of an old established order, which changed forever with the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. It's also something of an ominous warning of what was to come in the 20th century, just a few short years away, and the atrocity which no one could have contemplated.

I included some of the most important passages from the introduction below, as I think they do an admirable job of describing and defining "Gothic," a term not well understood in the modern sense, aside perhaps from the systematic challenging and transgression of borders and boundaries, where rules break down and life is lived in the margins. This is a worthwhile volume with some truly spooky and unsettling tales, well worth a read if you're a fan of suspense fiction: it certainly highlights the anxieties and insecurities of people of the period, who faced an evermore speedily changing world.

--------Important Passages--------

The Gothic repeatedly stages moments of transgression because it is obsessed with establishing and policing borders, delineating strict categories of being. The enduring icons of the Gothic are entities that breach the absolute distinctions between life and death (ghosts, vampires, mummies, zombies, Frankenstein's creature) or between human and beast (werewolves and other animalistic regressions, the creatures spliced together by Dr. Moreau) or which threaten the integrity of the individual ego and the exercise of will by merging with another (Jeckyll and Hyde, the persecuting double, the Mesmerist who holds victims in his or her power). Ostensibly, conclusions reinstate fixed borders, re-secure autonomy, and destroy any intolerable occpants of these twilight zones.

The most succssful mosters overdetermine these tansgressions to become, in Judith Halberstam's evocative phrase, 'technologies of monstrosity' that condense and process different and even contradictory anxieties about category and border. Some critics hold that the genre speaks to universal, primitive taboos about the very foundational elements of what it means to be human, yet the ebb and flow of the Gothic across the modern period invites more historical readings. Indeed, one of the princial border breaches in the Gothic is history itself- the insidious leakage of the pre-modern past into the skeptical, allegedly enlightened present. The Gothic, Robert Mighall suggests, can be thought of as a way of relating to the past and its legacies.

We can think about this in fairly abstract ways: the ghost, for instance, is structurally a stubborn trace of the past that persists into the present and demands a historical understanding if it is to be laid to rest. Similarly, Sigmund Freud defined the feeling of the uncanny as the shiver of realizing that modern reason has merely repressed rather than replaced primitive superstition. 'All supposedly educated people have ceased to believe officailly that the dead can become visible as spirits', yet Freud suspeccted that at times 'almost all of us think as savages do on this topic.' This return to pre-modern beliefs was itself the product of thinking of human subjectivity as a history of developmental layers that could be stripped away in an instant of dread, returning us to a 'savage' state.