Helpful Score: 2

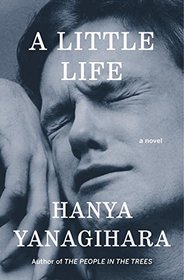

Once in a great while, a book comes along that finds a permanent place in my heart. That is where A Little Life resides, along with The Elegance of the Hedgehog, A Prayer for Owen Meany and a few others. This novel celebrates the power of love and friendship, and the resilience of the human spirit in the aftermath of devastating, heartbreaking betrayals. This is life at its grittiest and, subsequently, at its most sublime. There is cruelty in this book that left me in tears, but there is also an extraordinary depth of kindness and compassion. This is a difficult book to put down once begun and, despite its length, I was so sorry to see it end. 720 pages simply wasn't enough. This is a powerful story by a profoundly talented writer.

Helpful Score: 1

I didn't like this.

I found every page of the 115 I read painfully empty and self-indulgent, and the prospect of 600-odd more pages of the same was mind-numbingly awful. "Taking a break" from it felt like a blessed relief, and gradually turned into abandonment, and I have no regrets.

Yanagihara has said, in interviews, that her objective was to ask, what if there are some people who are just too damaged to save? I'd like to flip that on its head an ask, what if an all-powerful being (the Author) inflicts three useless, selfish "friends" on one who has suffered terrible abuse? And then the author heaps as much abuse as possible on that person, in order to make it impossible for them to be saved?

What if the "friends" are contrived to be as incestuously close and inward looking as it might be possible to be, with little connection to their families, and very little connection to any other friends or colleagues? They stay stuck in the close-knit little foursome they form as college roommates, all obsessing about (but never really helping) their damaged but brilliant friend, Jude.

I've read several times comparisons to Mary McCarthy's novel The Group, and that occurred to me, as I read the blurb, and weighed this brick of a book in my hand -- four brilliant young men, with issues, take on the world, and the world kicks back at them. It's a long time since I read The Group, and my memory of the novel may be tainted by the movie adaptation, but my strongest recollection is that the women in that novel was that it certainly wasn't a great novel, but it was a page-turner, and it had a certain horrible fascination as a sort of "state of the [female] nation" social document: the member of the group were avatars of the negative possibilities of female experience of its time, representative of, and victims of, the injustices and horrors of female experience. See Friend A survive an abortion, Friend B kill herself over an unworthy man, Friend C, a stay at home mom, dumped by her husband for a younger model ... etc

There's nothing like that here. Jude is Job, the recipient of all the ills of the world,, but his friends are not fully realized, recognizable people, but clueless, self-centred cyphers, like shapes cut by the same cookie-cutter: handsome, smart in a superficial way, stumbling into inexplicable success at something that they don't seem to be all that good at. Vaguely described, and a bit fuzzy round the edges -- two are supposed to be black (but don't seem like it). Two are supposed to be poor (but never really seem like that, either) Unmoored: either conveniently free of families, or dismissive of any claims their families have on them.

The narrative is also unmoored, and several interviewers, reviews, and readers have commented on this -- there is nothing to peg the narrative to a specific time. Sometimes it feels like the 1950s, and then someone whips our a cellphone; sometimes, it feels like now, but there's no mention of 9/11, Donald Trump, the ban on smoking in restaurants, Hurricane Sandy -- all topics that a New Yorker might at any time in the past 20 years have been affected by or had an opinion about ...

Some reviewers have referred to this, admiringly, as Yanagihara refusing to be distracted from her character (and Jude's suffering) by such trivial concerns as real life. Some have said that the novel exists in a sort of alternative reality in which those things didn't happen. (I read Science Fiction, mate. I know alternative reality, I like alternative reality, and this, sir, is no alternative reality ...)

What I think is that Yanagihara is a lazy writer, whose characters would be revealed as purest cardboard, with no life outside the narrow boundaries she has given them, if she tried to force them to relate to challenging, cataclysmic events.

I think the Emperor has no clothes.

I found every page of the 115 I read painfully empty and self-indulgent, and the prospect of 600-odd more pages of the same was mind-numbingly awful. "Taking a break" from it felt like a blessed relief, and gradually turned into abandonment, and I have no regrets.

Yanagihara has said, in interviews, that her objective was to ask, what if there are some people who are just too damaged to save? I'd like to flip that on its head an ask, what if an all-powerful being (the Author) inflicts three useless, selfish "friends" on one who has suffered terrible abuse? And then the author heaps as much abuse as possible on that person, in order to make it impossible for them to be saved?

What if the "friends" are contrived to be as incestuously close and inward looking as it might be possible to be, with little connection to their families, and very little connection to any other friends or colleagues? They stay stuck in the close-knit little foursome they form as college roommates, all obsessing about (but never really helping) their damaged but brilliant friend, Jude.

I've read several times comparisons to Mary McCarthy's novel The Group, and that occurred to me, as I read the blurb, and weighed this brick of a book in my hand -- four brilliant young men, with issues, take on the world, and the world kicks back at them. It's a long time since I read The Group, and my memory of the novel may be tainted by the movie adaptation, but my strongest recollection is that the women in that novel was that it certainly wasn't a great novel, but it was a page-turner, and it had a certain horrible fascination as a sort of "state of the [female] nation" social document: the member of the group were avatars of the negative possibilities of female experience of its time, representative of, and victims of, the injustices and horrors of female experience. See Friend A survive an abortion, Friend B kill herself over an unworthy man, Friend C, a stay at home mom, dumped by her husband for a younger model ... etc

There's nothing like that here. Jude is Job, the recipient of all the ills of the world,, but his friends are not fully realized, recognizable people, but clueless, self-centred cyphers, like shapes cut by the same cookie-cutter: handsome, smart in a superficial way, stumbling into inexplicable success at something that they don't seem to be all that good at. Vaguely described, and a bit fuzzy round the edges -- two are supposed to be black (but don't seem like it). Two are supposed to be poor (but never really seem like that, either) Unmoored: either conveniently free of families, or dismissive of any claims their families have on them.

The narrative is also unmoored, and several interviewers, reviews, and readers have commented on this -- there is nothing to peg the narrative to a specific time. Sometimes it feels like the 1950s, and then someone whips our a cellphone; sometimes, it feels like now, but there's no mention of 9/11, Donald Trump, the ban on smoking in restaurants, Hurricane Sandy -- all topics that a New Yorker might at any time in the past 20 years have been affected by or had an opinion about ...

Some reviewers have referred to this, admiringly, as Yanagihara refusing to be distracted from her character (and Jude's suffering) by such trivial concerns as real life. Some have said that the novel exists in a sort of alternative reality in which those things didn't happen. (I read Science Fiction, mate. I know alternative reality, I like alternative reality, and this, sir, is no alternative reality ...)

What I think is that Yanagihara is a lazy writer, whose characters would be revealed as purest cardboard, with no life outside the narrow boundaries she has given them, if she tried to force them to relate to challenging, cataclysmic events.

I think the Emperor has no clothes.