Search -

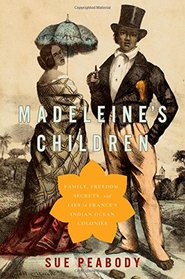

Madeleine's Children: Family, Freedom, Secrets, and Lies in France's Indian Ocean Colonies

Madeleine's Children Family Freedom Secrets and Lies in France's Indian Ocean Colonies

Author:

In 1759 a baby girl was born to an impoverished family on the Indian subcontinent. Her parents pawned her into bondage as a way to survive famine. A Portuguese slaver sold the girl to a pious French spinster in Bengal, where she was baptized as Madeleine. Eventually she was taken to France by way of Ile de France (Mauritius), and from there to I... more »

Author:

In 1759 a baby girl was born to an impoverished family on the Indian subcontinent. Her parents pawned her into bondage as a way to survive famine. A Portuguese slaver sold the girl to a pious French spinster in Bengal, where she was baptized as Madeleine. Eventually she was taken to France by way of Ile de France (Mauritius), and from there to I... more »

ISBN-13: 9780190233884

ISBN-10: 0190233885

Publication Date: 5/25/2017

Pages: 352

Rating: ?

ISBN-10: 0190233885

Publication Date: 5/25/2017

Pages: 352

Rating: ?

0 stars, based on 0 rating

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Book Type: Hardcover

Members Wishing: 2

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Book Type: Hardcover

Members Wishing: 2

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Genres:

- History >> Asia

- History >> Europe

- History >> Military >> Naval

- History >> World

- Nonfiction >> Transportation >> Ships >> History

- Nonfiction >> Social Sciences >> Discrimination & Racism

- Uncategorized >> International & World Politics >> Asian

- Uncategorized >> International & World Politics >> European

- Politics & Social Sciences >> Politics & Government >> Specific Topics >> Colonialism & Post-Colonialism