Search -

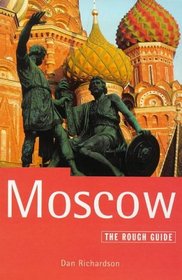

Moscow 2: The Rough Guide, 2nd edition (Rough Guides)

Moscow 2 The Rough Guide 2nd edition - Rough Guides

Author:

Introduction Moscow is all things to all people. In Siberia, they call it "the West", with a note of scorn for the bureaucrats and politicians who promulgate and posture in the capital. For Westerners, the city may look European, but its unruly spirit seems closer to Central Asia. To Muscovites, however, Moscow is both a "Mother City" and a "bi... more »

Author:

Introduction Moscow is all things to all people. In Siberia, they call it "the West", with a note of scorn for the bureaucrats and politicians who promulgate and posture in the capital. For Westerners, the city may look European, but its unruly spirit seems closer to Central Asia. To Muscovites, however, Moscow is both a "Mother City" and a "bi... more »

ISBN-13: 9781858283227

ISBN-10: 1858283221

Publication Date: 11/1/1998

Pages: 410

Edition: 2nd

Rating: ?

ISBN-10: 1858283221

Publication Date: 11/1/1998

Pages: 410

Edition: 2nd

Rating: ?

0 stars, based on 0 rating

Genres:

- Travel >> Asia >> Russia >> General

- Travel >> Asia >> Russia >> Moscow

- Travel >> Europe >> General

- Travel >> Reference >> Guidebooks

- Travel >> Travel Writing

- Travel >> Guidebook Series >> Rough Guide