Search -

The Surrendered

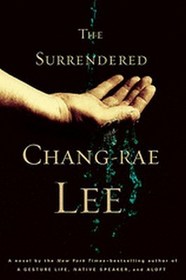

The Surrendered

Author:

Lee's masterful fourth novel (after Aloft) bursts with drama and human anguish as it documents the ravages and indelible effects of war. June Han is a starving 11-year-old refugee fleeing military combat during the Korean War when she is separated from her seven-year-old twin siblings. Eventually brought to an orphanage near Seoul by ... more »

Author:

Lee's masterful fourth novel (after Aloft) bursts with drama and human anguish as it documents the ravages and indelible effects of war. June Han is a starving 11-year-old refugee fleeing military combat during the Korean War when she is separated from her seven-year-old twin siblings. Eventually brought to an orphanage near Seoul by ... more »

The Market's bargain prices are even better for Paperbackswap club members!

Retail Price: Buy New (Hardcover): $18.39 (save 31%) or

Become a PBS member and pay $14.49+1 PBS book credit

![header=[] body=[Get a free book credit right now by joining the club and listing 5 books you have and are willing to share with other members!] Help icon](/images/question.gif?v=29befa08) (save 46%)

(save 46%)ISBN-13: 9781594489761

ISBN-10: 1594489769

Publication Date: 4/1/2008

Pages: 352

Rating: 11

ISBN-10: 1594489769

Publication Date: 4/1/2008

Pages: 352

Rating: 11

3.2 stars, based on 11 ratings

Publisher: Riverhead Hardcover

Book Type: Hardcover

Other Versions: Paperback, Audio CD

Members Wishing: 8

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Book Type: Hardcover

Other Versions: Paperback, Audio CD

Members Wishing: 8

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Genres:

- Literature & Fiction >> General >> Contemporary

- Literature & Fiction >> General >> Literary

- Literature & Fiction >> World Literature >> United States >> Asian American & Pacific Islander >> General

- Literature & Fiction >> World Literature >> United States >> Asian American & Pacific Islander >> Lee-Chang-Rae