Helpful Score: 8

Honestly, I was a little disappointed with this book. I have read many books on this subject and..I don't know...the information in the book was very informative, but the style in which it was written, I just did not care for. It was actually hard for me to get through the entire book, because of the writing style and not the content.

Marianna S. (Angeloudi) reviewed This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen on + 160 more book reviews

Helpful Score: 6

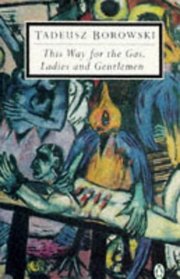

The somewhat macabre title is a good intro to this book of short stories by Tadeusz Borowski, a Polish "Aryan" (i.e. non-Jewish) prisoner in Auschwitz and Birkenau. By the time he arrived in camp, they were no longer routinely executing "Aryan" prisoners, but only Jews. His matter-of-fact descriptions- of the most mundane occurences, as well as the most horrific, leaves the reader with a sense of unreality. How can this man, who survived and witnessed the most horrendous examples of cruelty, torture, mass executions, and inhumanity, write these stories which include examples of wry humorous observations of the prisoner's foibles and hopes for the future?

This is not an easy read- the subject matter is truly barbaric- but it is very worth reading. Borowski, a concentration camp victim himself, understood what human beings will do to endure the unendurable. These stories, considered a masterpiece of Polish Literature, stand as cruel testimony to the level of inhumanity of which man is capable.

Unfortunately, Borowski ended his own life by his own hand in 1951, 6 years after surviving his three years of slave labor in the camps.

This is not an easy read- the subject matter is truly barbaric- but it is very worth reading. Borowski, a concentration camp victim himself, understood what human beings will do to endure the unendurable. These stories, considered a masterpiece of Polish Literature, stand as cruel testimony to the level of inhumanity of which man is capable.

Unfortunately, Borowski ended his own life by his own hand in 1951, 6 years after surviving his three years of slave labor in the camps.

Helpful Score: 4

This was really a horrific account of daily life in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. Borowski's "This Way for the Gas" is actually a collection of stories which detail the brutality and gruesomeness of the Holocaust. Borowski was from Poland but he was not Jewish so he received better treatment in the camps and he tells the stories in a very matter-of-fact language. Some of the details portrayed by Borowski will leave you haunted. Ironically, Borowski committed suicide several years after his experiences by putting his head in a gas oven probably over guilt and remorse related to his experiences. I would highly recommend this book - it is a remarkable read, very profound and overwhelming.

Helpful Score: 3

All of the stories in this book are touching with some being far more powerful and unforgettable than others.

I think for a person who devours any and all books on the Holocaust this is a good addition but for someone who reads less on the subject this probably isn't a great one to add.

I can think of a dozen (or more) books I'd recommend before this one.

I think for a person who devours any and all books on the Holocaust this is a good addition but for someone who reads less on the subject this probably isn't a great one to add.

I can think of a dozen (or more) books I'd recommend before this one.

Helpful Score: 2

Borowski survived both Auschwitz and Dachau to marry, write, and work for the Polish government. This slim volume contains a dozen powerful short stories that stand alongside Elie Wiesel's as clear-eyed testaments.

![header=[] body=[Get a free book credit right now by joining the club and listing 5 books you have and are willing to share with other members!] Help icon](/images/question.gif?v=29befa08)