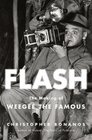

Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

Author:

Genres: Arts & Photography, Biographies & Memoirs, Humor & Entertainment

Book Type: Hardcover

Author:

Genres: Arts & Photography, Biographies & Memoirs, Humor & Entertainment

Book Type: Hardcover

Leo T. reviewed on + 1775 more book reviews

I obtained the book at the library after reading the excellent essay reviewing it in The New Yorker. Thomas Mallon, 'Weegee's Nocturnal Photography,' pp. 64-70, 28 May 2018. Mr. Bonanos offers excellent scholarship and has ferreted out excellent detail on the life of Arthur Fellig. It is actually more detail than I myself am interested in, although I have recognized and admired Weegee's photos for many years.

Mr. Fellig was a tireless self-promoter, a very good attribute in his line of work. He came up just as newspapers expanded the use of photogravure work. The author includes good background information such as his brief discourse on the attributes of the Speed Graphic and of the newspaper business in the days of more than one edition and competing papers, especially in NYC. I myself had forgotten that Bernarr Macfadden founded the Evening Graphic, in the past being reminded of him when his long surviving widow attended formal dinners as a guest of the Weider brothers. The Daily News launched the tabloid, aimed to sell papers to workingmen, in 1919 and "at its peak, twenty years after that, it was printing 4.7 million every Sunday, a volume no American newspaper has ever matched or ever will again."

The Graphic ran the columns of Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan. The Daily Mirror (1924) was W.R. Hearst's very competitive entry into the tabloid wars.

Weegee began by selling tintypes door to door as a youth, caught on in 1921 as a dark room assistant at the NY Times (they had launched their World Wide Pictures service), moved to the NY World, then Keystone, and wound up as a stringer for the Acme Newspictures in 1924. It was years before photos were credited (and few stories were credited either) so the product of his early years is not identifiable. The entire autobiography testifies to Weegee's never ending hard work and search for glory.

Mr. Bonanos notes that he was making $5 for each photo sold (and being the first to have a print on offer was vital, especially with crime scenes) and while he must have had bad days, that was a half eagle in gold then. He did fill in slow times with staged topical photos, such as kids sleeping on the fire escape in hot weather. Don't we all remember the photo of the kid frying an egg on the sidewalk or the elephant helping pull the broken down truck out of traffic as Ringling Bros. arrived in town? Chapter 7 offers a good example of his work from 1937. He was 'on call' for the Journal when Father Divine was arrested, questioned, and bailed out, with Weegee capturing photos inside the police station and "departed for the 115th Street Heaven in his immense Rolls-Royce as parishioners chanted and cheered." That series of photos was sold all over the country. Weegee also was able to sell to Life magazine (and then Look) when it launched--many photographers could not handle the 'story' type photos that were needed instead of 'static' newspaper pictures. An example offered by Bonanos is a 1943 'drag' photo and a sample of Bonanos' writing. "A headline writer, giving the picture a title that Weegee himself later used, referred to him as 'Myrtle from Myrtle Avenue.' In real life, he was a mugger named Donald Gill, a man who'd cross-dressed in order to sneak up on his potential victims. He'd been caught when he chatted up the male half of a Brooklyn then (in the words of a Post reporter) 'began punching him in a very competent and unladylike manner.' He turned out to to be3 a newly discharged soldier with a rap sheet for burglary and larceny."

Weegee postwar days trying to catch on in Hollywood are rather sad, but it can be said he did span the era, knowing both Alfred Stieglitz and Andy Warhol.

Excellent endnotes, index, and a few representative photos.

Mr. Fellig was a tireless self-promoter, a very good attribute in his line of work. He came up just as newspapers expanded the use of photogravure work. The author includes good background information such as his brief discourse on the attributes of the Speed Graphic and of the newspaper business in the days of more than one edition and competing papers, especially in NYC. I myself had forgotten that Bernarr Macfadden founded the Evening Graphic, in the past being reminded of him when his long surviving widow attended formal dinners as a guest of the Weider brothers. The Daily News launched the tabloid, aimed to sell papers to workingmen, in 1919 and "at its peak, twenty years after that, it was printing 4.7 million every Sunday, a volume no American newspaper has ever matched or ever will again."

The Graphic ran the columns of Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan. The Daily Mirror (1924) was W.R. Hearst's very competitive entry into the tabloid wars.

Weegee began by selling tintypes door to door as a youth, caught on in 1921 as a dark room assistant at the NY Times (they had launched their World Wide Pictures service), moved to the NY World, then Keystone, and wound up as a stringer for the Acme Newspictures in 1924. It was years before photos were credited (and few stories were credited either) so the product of his early years is not identifiable. The entire autobiography testifies to Weegee's never ending hard work and search for glory.

Mr. Bonanos notes that he was making $5 for each photo sold (and being the first to have a print on offer was vital, especially with crime scenes) and while he must have had bad days, that was a half eagle in gold then. He did fill in slow times with staged topical photos, such as kids sleeping on the fire escape in hot weather. Don't we all remember the photo of the kid frying an egg on the sidewalk or the elephant helping pull the broken down truck out of traffic as Ringling Bros. arrived in town? Chapter 7 offers a good example of his work from 1937. He was 'on call' for the Journal when Father Divine was arrested, questioned, and bailed out, with Weegee capturing photos inside the police station and "departed for the 115th Street Heaven in his immense Rolls-Royce as parishioners chanted and cheered." That series of photos was sold all over the country. Weegee also was able to sell to Life magazine (and then Look) when it launched--many photographers could not handle the 'story' type photos that were needed instead of 'static' newspaper pictures. An example offered by Bonanos is a 1943 'drag' photo and a sample of Bonanos' writing. "A headline writer, giving the picture a title that Weegee himself later used, referred to him as 'Myrtle from Myrtle Avenue.' In real life, he was a mugger named Donald Gill, a man who'd cross-dressed in order to sneak up on his potential victims. He'd been caught when he chatted up the male half of a Brooklyn then (in the words of a Post reporter) 'began punching him in a very competent and unladylike manner.' He turned out to to be3 a newly discharged soldier with a rap sheet for burglary and larceny."

Weegee postwar days trying to catch on in Hollywood are rather sad, but it can be said he did span the era, knowing both Alfred Stieglitz and Andy Warhol.

Excellent endnotes, index, and a few representative photos.